Page 99 - 卫星导航2021年第1-2合期

P. 99

Shinghal and Bisnath Satell Navig (2021) 2:10 Page 2 of 17

position-velocity–time and limited satellite informa- smartphone, and the RMS positioning errors were ~ 10 m

tion, such as the elevation and azimuth (Guo et al. 2020). in the north (N) and east (E) directions and ~ 20 m in the

Te positioning solution ofered by the phone typi- vertical. Wu et al. (2019) processed GNSS measurements

cally reached 2–3 m and degraded to tens or hundreds from a Xiaomi MI 8 smartphone in the dual-frequency

of meters in high noise and multipath environments. In PPP mode and obtained RMS positioning errors in the E,

2016, Google introduced the availability of raw GNSS N, and up (U) directions of 21.8, 4.1, and 11.0 cm, respec-

measurements for smartphones with Android N and sub- tively. However, it took 102 min for the three-dimen-

sequent versions and permitted duty cycling (a power- sional positioning error to converge to 1 m. Aggrey et al.

saving mechanism) to be turned of, ensuring continuous (2020) obtained an average horizontal error of 40 cm

tracking of raw GNSS measurements. In 2018, the world’s for dual-frequency PPP processing using the Xiaomi MI

frst dual-frequency GNSS-enabled smartphone, the 8, with a convergence time of 38 min in ideal open sky

Xiaomi MI 8, equipped with a Broadcom BCM47755 environments.

chipset was launched. It is capable of tracking L1/E1 and Most GNSS smartphone positioning tests typically

L5/E5 code and carrier-phase signals from GPS, Galileo have been carried out in static, open-sky, ideal condi-

Navigation Satellite System (Galileo) and Quasi-Zenith tions with the phone placed fat on rooftops. Tese data

Satellite System (QZSS) and single-frequency measure- collection methods and environments are far from those

ments from GLObal NAvigation Satellite System (GLO- of actual phone usage, which is mostly in the kinematic

NASS) L1 code and BeiDou Navigation Satellite System mode in sub-urban and urban environments with signal

(BDS) B1 code (EGSA 2018). blockages due to holding the phone in hand and refec-

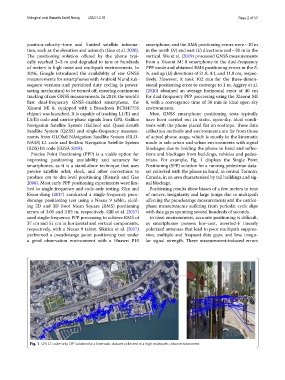

Precise Point Positioning (PPP) is a viable option for tions and blockages from buildings, vehicles and pedes-

improving positioning availability and accuracy for trians. For example, Fig. 1 displays the Single Point

smartphones, as it is a stand-alone technique that uses Positioning (SPP) solution for a running pedestrian data-

precise satellite orbit, clock, and other corrections to set collected with the phone in hand, in central Toronto,

produce cm to dm-level positioning (Bisnath and Gao Canada, in an area characterised by tall buildings and sig-

2008). Most early PPP positioning experiments were lim- nal blockage.

ited to single-frequency and code-only testing. Gim and Positioning results show biases of a few meters to tens

Kwon-dong (2017) conducted a single-frequency pseu- of meters, irregularity and large jumps due to multipath

dorange positioning test using a Nexus 9 tablet, yield- afecting the pseudorange measurements and the carrier-

ing 2D and 3D Root Mean Square (RMS) positioning phase measurements sufering from periodic cycle slips

errors of 3.05 and 3.82 m, respectively. Gill et al. (2017) with data gaps spanning several hundreds of seconds.

used single-frequency PPP processing to achieve RMS of In ideal environments, accurate positioning is difcult,

37 cm and 51 cm in horizontal and vertical components, as smartphones possess low-cost, inverted-F linearly

respectively, with a Nexus 9 tablet. Sikirica et al. (2017) polarized antennas that lead to poor multipath suppres-

performed a pseudorange point positioning test under sion, multiple and frequent data gaps, and low, irregu-

a good observation environment with a Huawei P10 lar signal strength. Tese measurement-induced errors

Fig. 1 GPS L1 code-only SPP solution for a kinematic dataset collected in a high multipath, urban environment